House In La Vicentina

ARCHITECTS

Al Borde

ARCHITECTURE AND CONSTRUCTION

Al Borde

AL BORDE CONTRIBUTORS

María Fernanda Heredia, Melissa Narváez

SUSTAINABILITY

Grupo Investigación Scinergy

SCINERGY CONTRIBUTORS

Estefany Vizuete, Joel Vega

STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

Patricio Cevallos

PLUMBING

Carolina Quishpe

PHOTOGRAPHS

JAG Studio

YEAR

2024

LOCATION

Quito, Ecuador

CATEGORY

Houses

English description provided by the architects.

The project is located in La Vicentina, a traditional middle-class neighborhood in Quito, Ecuador.

The location of the lot on a staircase makes it impossible to have parking, but far from being a disadvantage, it aligns with the lifestyle of the owner, who is a frequent bicycle user.

In addition, the hillside topography provides an opportunity to take advantage of the view towards Cerro Auqui.

Added to these conditions are the client's needs: a home for his own use, a smaller one for his daughter, and a versatile common space that can function as a workshop or social area.

The house is the personal project of Freddy Ordóñez, a mechanical engineer, university professor, and director of the SCINERGY research group at the National Polytechnic School.

The project demonstrates the feasibility of building a resilient home in an urban area, whose strategies can be replicated in equatorial regions.

The house has become an integral part of his research. Equipped with sensors, it generates data that the group analyzes to verify its proper functioning.

BUILDING NEIGHBORHOODS

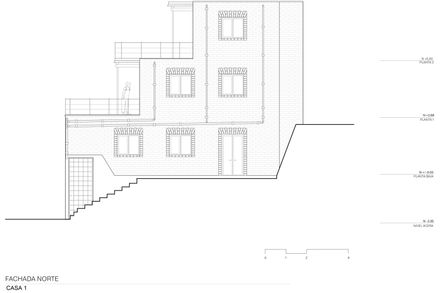

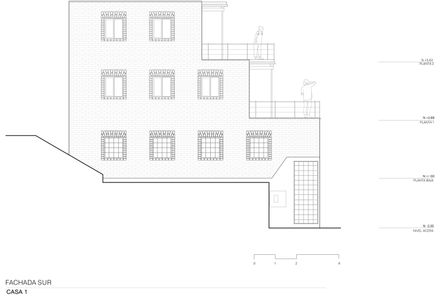

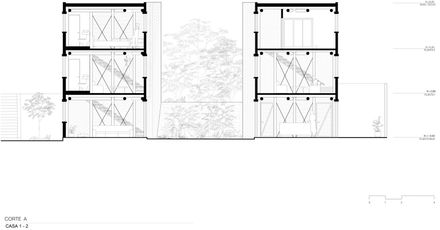

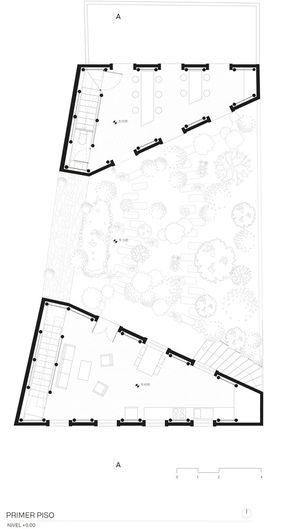

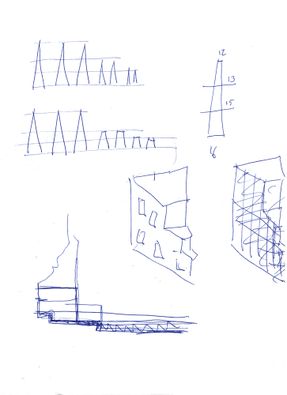

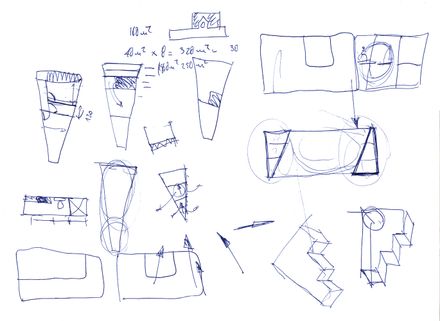

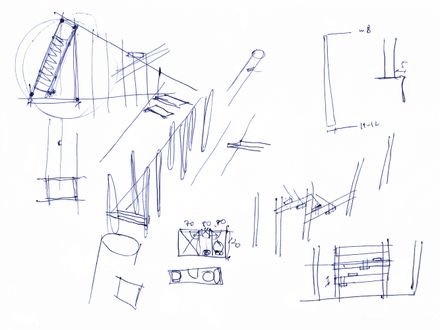

The shape of the project favors verticality to free up space on the ground floor. Two slender volumes are created to maximize the surface area of the courtyard.

This compacting operation generates a central courtyard that joins the neighboring courtyard, integrating the existing jacaranda tree.

The trapezoidal shape of the courtyard is the result of optimizing solar gain by reducing the eastern end and expanding the western end.

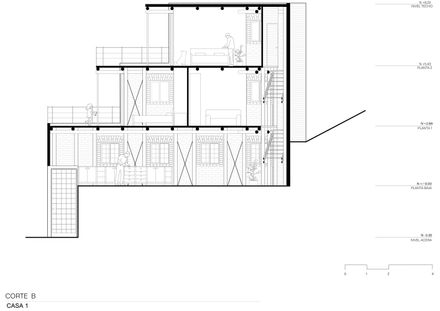

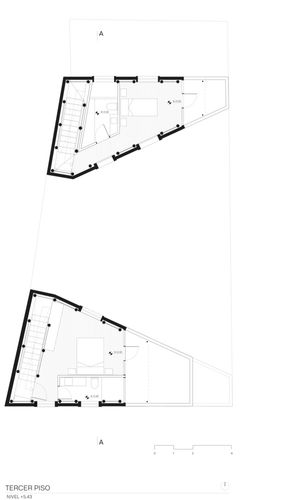

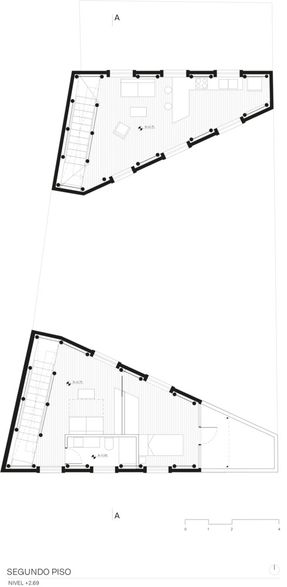

The narrowness of the floors means that each level is assigned a main function: the social area on the ground floor, a bedroom and a study on the first floor, and another bedroom on the second floor.

The progressive reduction in the area required on each level allows the floors to be set back, creating east-facing terraces. These terraces open up the view, capture solar radiation, connect with the neighborhood, and reinforce the relationship with the outside.

The absence of a perimeter wall between the street and the building, combined with the orientation of the windows toward the public space, is no coincidence.

These design decisions generate spontaneous community surveillance, where greater visibility deters criminal acts and, at the same time, promotes social interaction and strengthens the sense of community.

Thus, the architecture not only satisfies the client's need to connect with their neighborhood, but also becomes an active tool for building community.

WHAT THE ENVIRONMENT GIVES US

The presence of eucalyptus in the Quito landscape is a reminder of decisions made in the past and their long-term consequences.

Introduced to Ecuador in 1865 during the government of Gabriel García Moreno, eucalyptus was promoted as a fast-growing resource for construction and reforestation.

However, its invasive nature has had negative effects on the Andean ecosystem: eucalyptus forests expanded rapidly, preventing the growth of local species and eroding the soil.

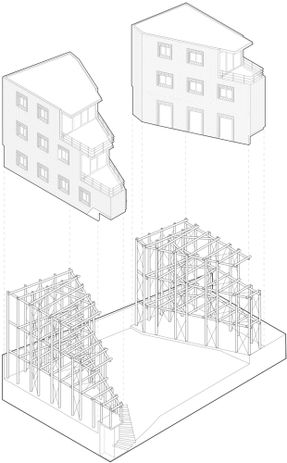

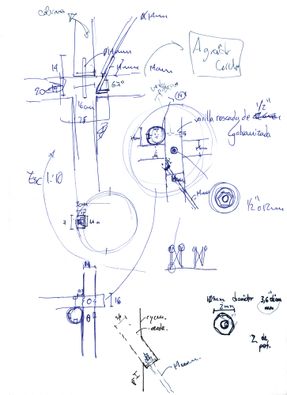

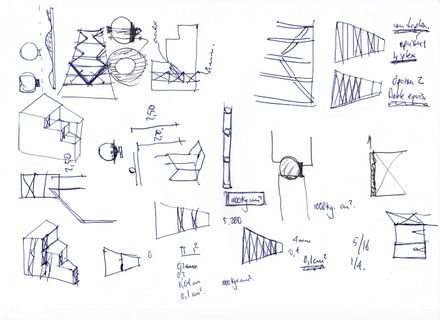

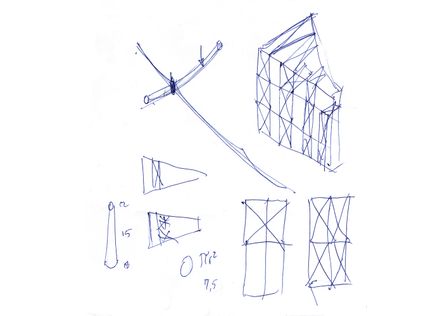

In this project, the columns are made of 9-meter-long pingos (eucalyptus logs), without this representing a complex technical requirement.

The logs were obtained from a nearby forest, 12.3 km from the site, where the owner is replacing eucalyptus trees with native species, thus restoring the ecological balance.

In addition, the proximity of the forest facilitates complete control of the process and traceability of the materials, aspects that are often complex in conventional construction.

Building with logs offers remarkable efficiency because it eliminates the need for wood processing and transformation.

Using the trunk in its natural state allows for maximum use of the material, reducing energy consumption and waste generated in industrialization, where the goal is to obtain orthogonal pieces of standard sizes.

As a result, choosing logs for the structure significantly reduces embodied and operational carbon emissions.

BRICK FACADE

The wood must be protected. Brick was chosen for this protection because of its resistance to weather conditions, but also because it provides something essential to the project:

the ability to capture heat, store it, and release it gradually. The facade is separated from the irregular, rough-hewn wood to facilitate construction.

The combination of brick and wood in a seismic zone such as Quito presented structural challenges. A 14 cm brick wall cannot support three floors on its own.

In this project, the aim is to combine both systems: the skeleton is constructed using pingos, while the brick provides rigidity.

Handmade bricks, produced in family-run brickworks, were chosen. This decision was not based on a lack of access to industrial bricks, but rather on a desire to support small local producers.

FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE

The house is an open laboratory for research. The design prioritizes passive thermal comfort, with strategies such as solar orientation, cross ventilation, thermal mass, and insulation in ceilings and floors, achieving 72% of hours of indoor thermal comfort in a city where homes rarely exceed 40% of hours of comfort per year.

The house also achieves net zero electricity consumption thanks to a photovoltaic system, the use of a heat pump for water heating, and reduced electricity consumption. Water consumption is also reduced by 40% through rainwater harvesting and gray water treatment.

Finally, the choice of eucalyptus wood for the structure, mezzanines, and roof, together with handmade brick for the masonry, reduces embedded carbon by 80% compared to conventional construction, according to ongoing studies.

The central courtyard of the house is designed as an infiltration space, which contributes to the recharge of the city's aquifers.

Every action counts, considering that water sources are becoming increasingly distant and that urban areas suffer more from water supply issues.

If, instead of relying solely on large infrastructure projects to address climate change in cities, projects involving small, replicable actions are promoted, the solution does not lie solely in massive government investment.

On the contrary, the sum of individual actions can reduce dependence on large-scale infrastructure, demonstrating how the micro can influence the macro.