Laoyuting Pavilion

ARCHITECTS

Atelier Deshaus

DESIGN TEAM

Liu Yichun, Shi Yujie, Ji Hongliang

CLIENT

Organizer Of The 2024 Dianchi Art Season In Kunming

STRUCTURAL DESIGN

Zhang Zhun, Pan Jun

COLLABORATORS

Roboticplus, And Office

PHOTOGRAPHS

Ce Wang

AREA

171 m²

YEAR

2024

LOCATION

Kunming, China

CATEGORY

Pavilion

English description provided by the architects.

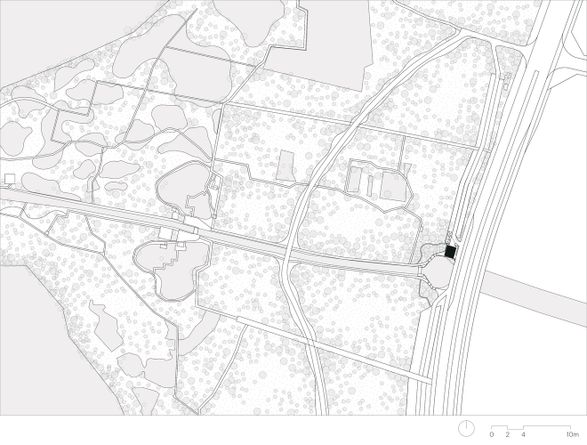

Laoyuting Pavilion is one of the invited projects of the 2024 Dianchi Art Season: "Home and Future". It is located on the southern side of the Water-Forest Art Zone in the Laoyu River Wetland Park at Dianchi Lake.

After its completion, it first served as the entrance to the Dianchi Art Festival, and after the festival, the pavilion was permanently preserved as a spatial hint for entering the wetland park, as well as a resting place for visitors.

This wetland, filled with groves of bald cypress along the edge of Dianchi Lake, is in fact part of the city's water-purification infrastructure—the final stage of natural filtration before water enters the lake.

It is home to many small fish, and city dwellers often come here during leisure time to catch fish, hence the name Laoyu River Wetland. As a pavilion where people rest while fishing, it naturally came to be known as the Laoyuting Pavilion.

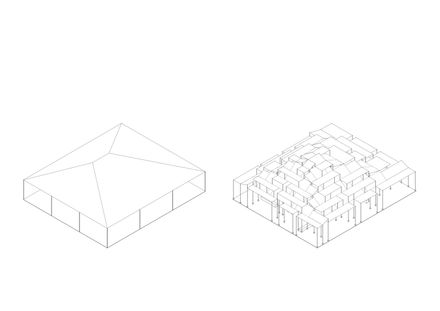

The pavilion uses slender steel columns and a fragmented roof to create an artificial "forest" between the busy roadway and the expanse of waterborne woodland.

A modern steel-structured pavilion is reinterpreted as a place offering an experience somewhere between "within the woods" and "beneath a primitive hut"—a threshold condition between the atmospheres of "nature" and "manmade."

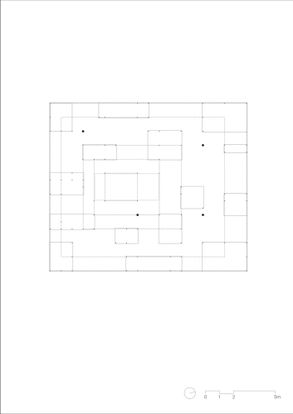

The dense 40 mm-diameter steel columns support a seemingly irregular roof, yet together they still form what can be called a ting, a pavilion.

Within the pavilion, among the staggered thin columns, two paths leading toward the deeper area of Dianchi Lake subtly unfold; people gather or disperse from here.

The roof allows fragmented light to enter, creating the sense of standing within deep shade, while glimpses of the sky and nearby treetops appear through the gaps.

From afar, however, the pavilion presents an image reminiscent of the four-sloped hipped roofs of traditional Chinese architecture. Yet, because the roof has been fragmented, it also takes on a thatched-roof-like appearance.

In this way, the actual material—steel plate—becomes dematerialized, or rather, its original industrial connotations are displaced.

This allows us to reconsider the relationship between technology and nature, as well as reexamine the relationship between the traditional Chinese ting and its natural landscape setting.

According to the environmental protection requirements of the Dianchi Wetland Park, the pavilion's foundation could not disturb the existing ground surface.

Thus, the structural base had to remain above ground. To achieve this, a steel plate was placed directly on the original surface as the pavilion's foundation.

Each column base is fixed atop a solid steel block of ten centimeters square, which acts as a localized "micro-foundation." After minor reinforcement, these small blocks support the cantilevered load of the slender columns, and their upward offset also suggests an intention to protect the original terrain.

To further minimize on-site disturbance, the pavilion's structure adopts a prefabricated and assembled system. All components—including columns, roof panels, joints, and bolts—were fabricated in the factory and then transported to the site for assembly.

This lightweight construction method made the entire building process akin to building a large outdoor installation rather than conducting conventional architectural construction.

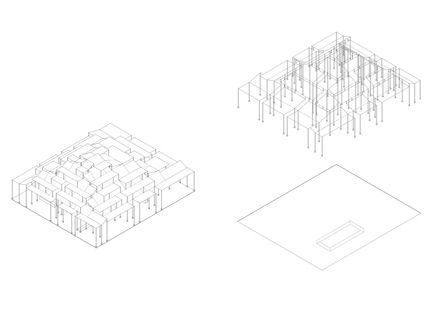

The Fishing Pavilion is formed by a basic structural module composed of "six columns + flat/sloped steel plates," with multiple modules overlapped and combined.

After superimposition, some columns are removed, and loads are transferred through thinner short columns connected to plates at higher levels, creating areas of differing column densities within the space—apparently random yet subtly intentional.

There are 93 ground-touching steel columns in total, each a 40 mm solid round bar working in cantilever. The flat plates and sloped plates are connected by hinges.

Above them, 125 short round steel columns of 20 mm diameter support additional flat and sloped plates, giving the roof a structural character somewhere between flexibility and rigidity.