Nedarag Guesthouse

ARCHITECTS

NextOffice–Alireza Taghaboni

LEAD ARCHITECT

Alireza Taghaboni

DESIGN TEAM

Niloufar Ghobadi, Hadi Ale Davoud, Ali Ghods, Meysam Feizi, Shanbeh Dehghani, Abdullah Dehghani, Mozammal Nohani, Zalour Nohani, Akram Nohani, Abdulrahim Delvashzehi, Mehrdad Makaremi, Sattar Ganjalipour, Masoud Soufiani, Farzad Ferasat,hadi Irani, Dorsa Sadeghi, Homa Asadi, Asal Karami, Marziyeh Norouzi, Ehsan Ahani

CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT

Residents Of The Village (Leaded By Shanbeh Dehghani), Hadi Ale-davood

SOCIAL FACILITATOR

Roostatish, Mina Kamran

PHOTOGRAPHS

Neel Studio, Ehsan Hajirasouliha

AREA

95 M²

YEAR

2024

LOCATION

Iran

CATEGORY

Hospitality Architecture

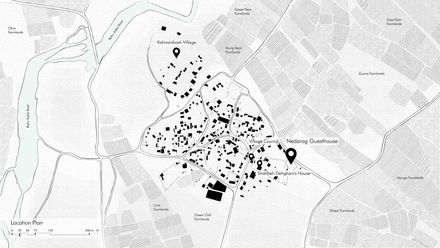

The Nedarag Guesthouse is a non-profit project situated in a remote village of roughly 200 households from the Sunni-Baluch minority in southeastern Iran.

In Iran's centralized and religiously homogeneous development system, ethnic and religious minorities are systematically excluded.

In villages like Kahnanikash, this marginalization is particularly severe due to the local practice of Zekri—a religious belief seen as heretical by the central government.

Ms. Kamran, a social facilitator who had previously worked with Mr. Shanbeh—our client and an influential villager—on building a bridge, library, and water purifier, proposed a multi-room guesthouse centered around Shanbeh's role.

The aim was to distribute the "blessings of hospitality" across the village. Prior to this, Shanbeh hosted travelers in a room of his own house.

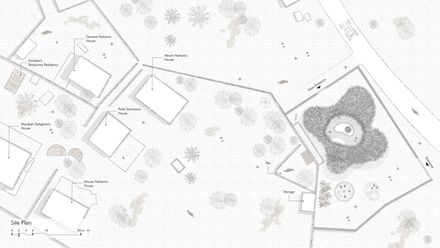

The land was donated by a villager named Heybatan Baluch and selected collaboratively by the design team, village elders, facilitator, and Shanbeh.

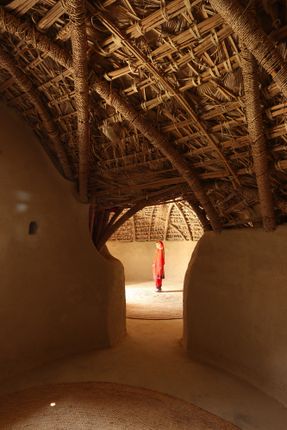

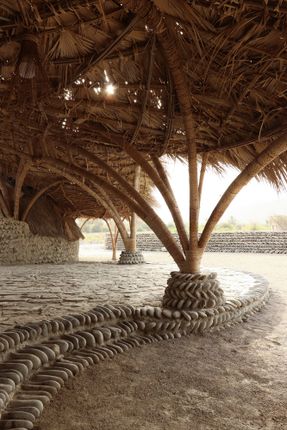

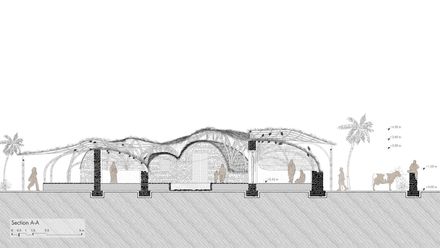

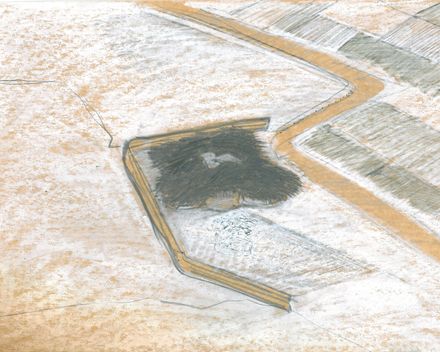

Positioned near farmlands, the site lies close to the village council and Shanbeh's home. The plan centers around a semi-open courtyard, shaded by a multilayered roof that enables passive cooling and airflow between and within rooms.

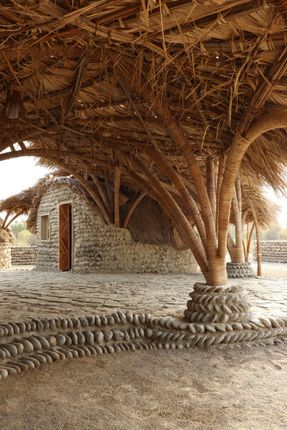

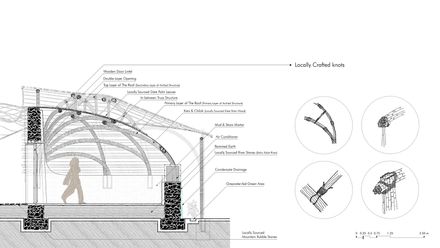

The design reinterprets the regional Kapar typology using handmade trusses in place of traditional beams to support a broad, umbrella-like roof. The double-layered roof and walls reduce thermal transfer.

Throughout, the team worked in continuous dialogue with local craftsmen to adapt and refine vernacular techniques.

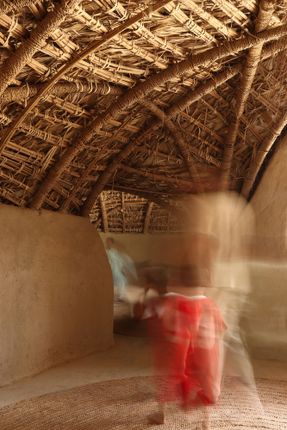

This fusion produced a distinct aesthetic through a contrast between the dome-like geometry of Iranian vaults and the imperfection of hand-built details; between the mass of thick stone walls and the lightness of the canopy; and painterly textures and details.

Construction was entirely collaborative. Over four months, villagers raised the stone walls; the Kapars were completed over the following year.

Funding came from the Nextoffice, a bank loan, a donation from Mr. Shanbeh, and contributions from other villagers—totaling approximately £8,000, well below typical construction costs.

As the construction was cooperative, instead of common surveying tools, the site layout was staked using strings and triangles in a game involving local children.

Elders wove palm-fiber ropes at night from Karz leaves gathered by youth, while women contributed to mat weaving, mud plastering, curtain sewing, and daily meals. These intergenerational efforts turned scarcity into resourcefulness.